A history of heat lamps

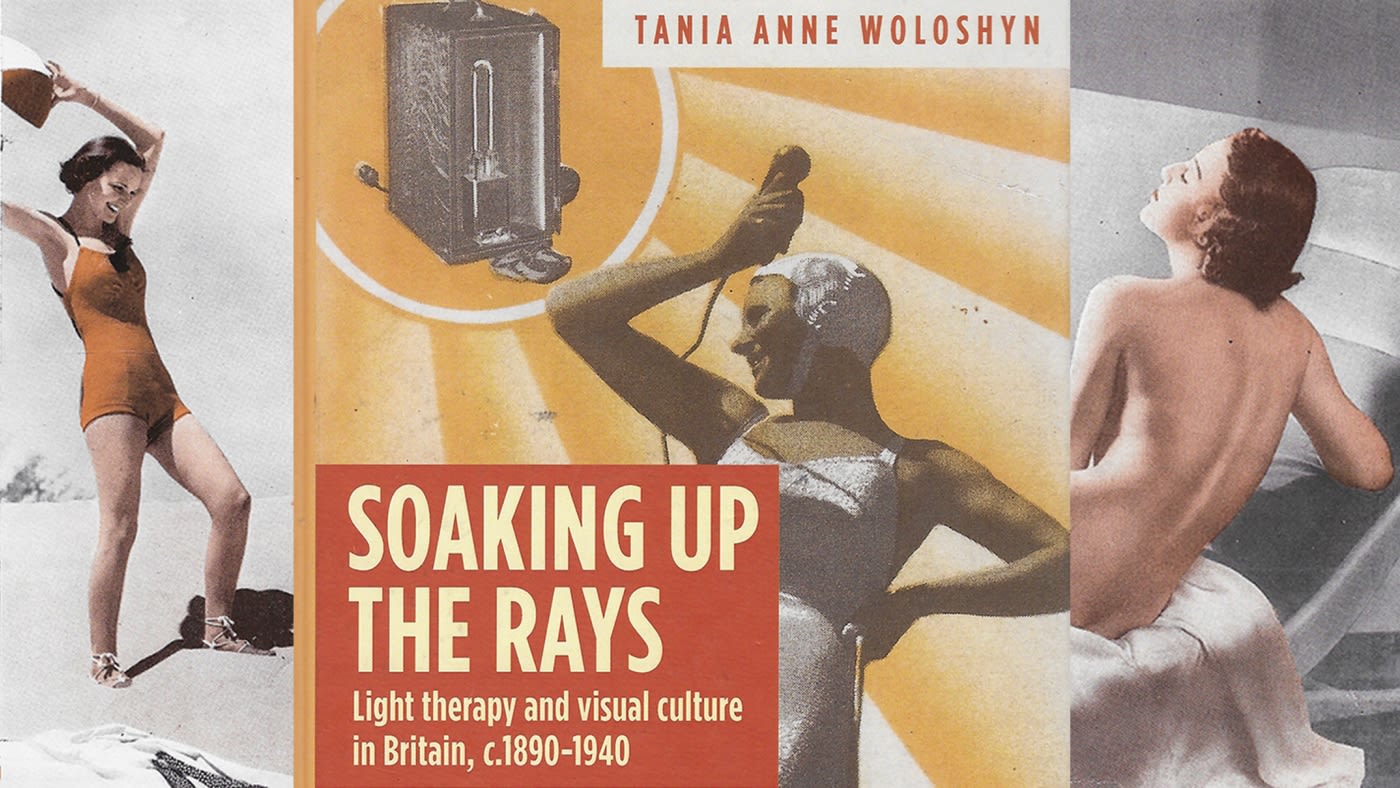

We’ve always been intrigued by heat lamps and their uses here at skinflint, and we’ve been lucky to salvage and restore many interesting examples of these unusual lights dating from the mid-century. Dr. Tania Woloshyn, author of 'Soaking up the Rays: Light Therapy and Visual Culture in Britain', became our expert-on-call for all things to do with heat lamps after we converted a piece from her private collection. We caught up with her to learn more about their fascinating history:

skinflint: How and when did the idea of light therapy come about?

Tania: The therapeutic use of light is as old as humankind. Several ancient civilisations worshipped the sun as a god (e.g. Ra for the ancient Egyptians, Apollo for the ancient Greeks). But the modern therapy that originated in the late 19th century took two main forms: natural sunlight, described as heliotherapy; and using electricity to produce artificial light via lamps, called phototherapy.

It is clear from medical literature in the 19th century that doctors were aware of the sun's heat being effective - a therapy which is still relied upon commonly today (hot water bottles, heating pads, creams that activate the sensation of heat, etc.). By 1870 scientists had proven that the sun could kill bacteria. But it was Niels Finsen (who won a Nobel Prize in 1903) who took that knowledge and applied it to treat bacterial infections: most famously tuberculosis of the skin (lupus vulgaris), a terrible disease that typically attacked the face. Finsen developed a special lamp with long arms and many lenses, through which he channeled blue, violet and ultraviolet rays, and he aimed them at patients' lesions. These rays killed the bacteria and stimulated the body to regenerate, allowing patients to heal. In a way this is the origin of the tanning bed!

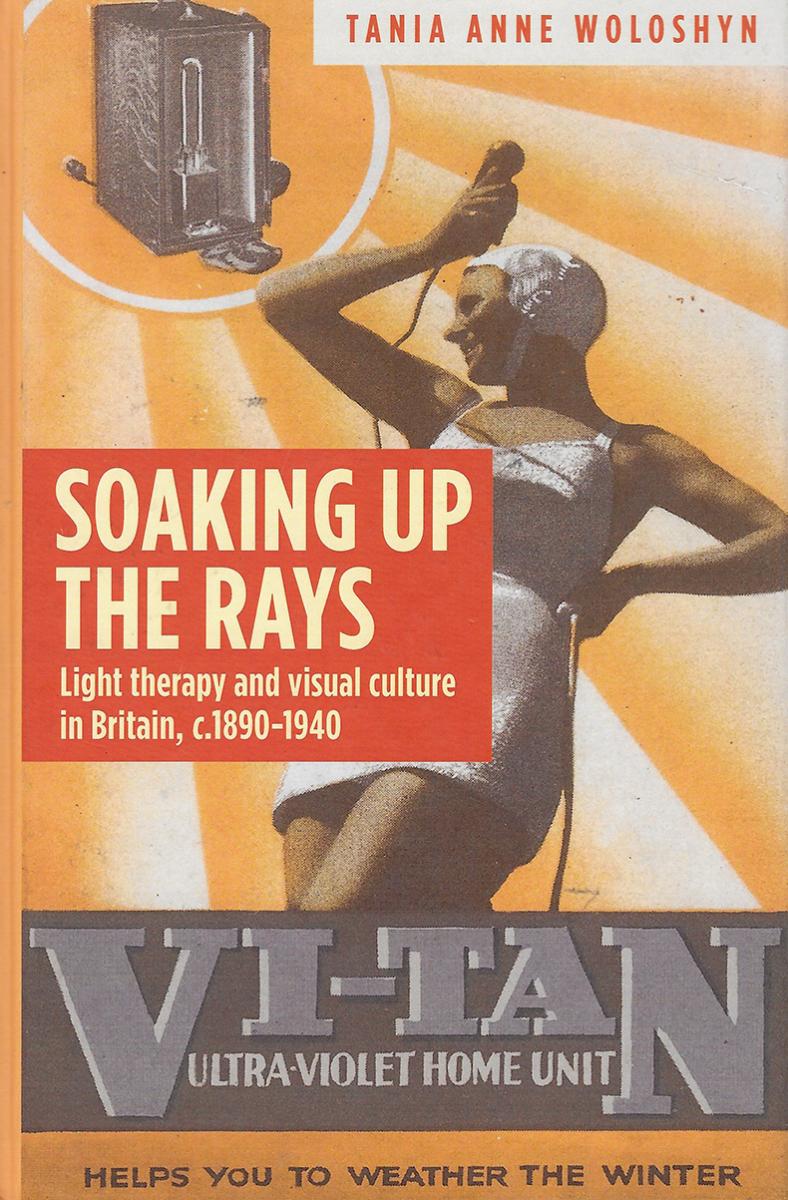

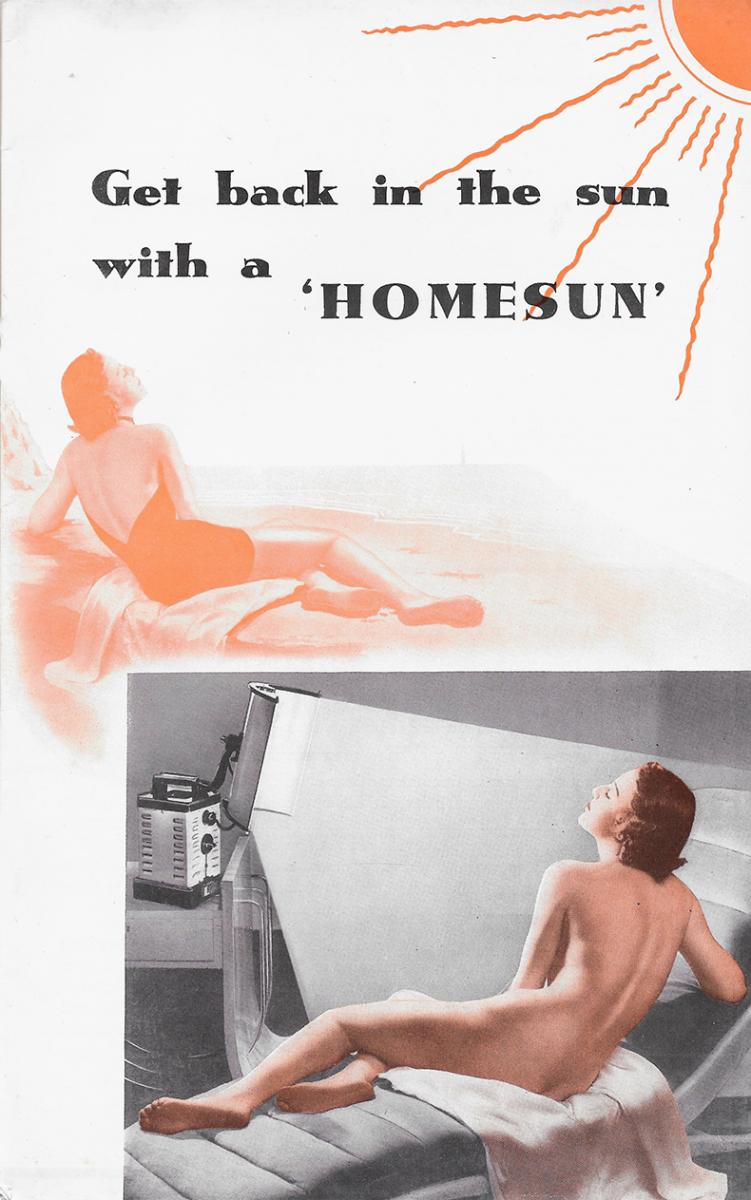

Above: Archive material from the Hanovia Homesun brand of heat lamps, published circa 1930.

What are the main differences between the light therapy and heat therapy lamps we convert? Are there others types?

Heat lamps used electrical coils (like an electric heater) or incandescent light bulbs (thank you, Edison!) to irradiate infrared and red rays, known as 'heat rays'. Like ultraviolet light on the other end of the spectrum, infrared light is invisible, but this light is the one we feel most intensely when we are outside in the sunshine: that sensation of heat on our skin is infrared light. Light therapists used heat/infrared lamps especially to speed the healing of injuries, because they knew that infrared penetrates deeply into the body and increases blood flow. The idea was the new blood would flush out toxins, moving things along to speed up recovery times. Of course it was also relied upon heavily for treating arthritis and sciatica too, because the heat is a known natural analgesic (pain reliever).

'Ultraviolet' lamps are the other type, but really the description is a misnomer: no bulb could produce solely ultraviolet light at this time, so it was always a combo of rays: infrared, visible light (so that it appeared white, when turned on), and ultraviolet. These were noisy, smelly and often dangerous objects: the carbon rods burned and spluttered hot ash, so it was important for users not to get too close to them. Goggles were also essential to protect the eyes!

Above: One of our converted heat lamps by 'Soltan' originating in the 1960s

Who used light therapy, and what conditions was it used to treat?

Heliotherapy and phototherapy (the latter also known as 'artificial sunlight therapy') were widely used during the first half of the 20th century to treat all manner of conditions. Mostly though, it was used for children who were suffering from anemia, malnourishment and pretty horrible forms of tuberculosis which could attack the spine, glands, bones and joints, causing tremendous pain, deformation and open wounds. In the late 1910s and early 1920s scientists discovered that sunlight could activate vitamin D production in the body, so during this time heliotherapy and phototherapy were used intensively to treat rickets, a childhood deficiency disorder caused by a lack of vitamin D.

In what ways the therapy administered?

Doctors who used heliotherapy or phototherapy were adamant that it be strictly monitored by professionals and followed by patients. They knew that overexposure caused sunburn and potentially heat exhaustion, which could be fatal for very weak and vulnerable patients. Auguste Rollier, one of the earliest and most well-known helio therapists, believed that patients should first be slowly acclimated to the sunshine; with the body slowly exposed, bit by bit, until patients could spend hours outside each day. Patients at his facilities in Leysin, in the Swiss alps, could spend years there. The children had lessons outside, skied and picked flowers, made crafts to sell, and ate wholesome foods and undertook remedial exercises. So Rollier used a combination of ‘natural’ treatments to help his patients.

Phototherapy could be administered in different ways, either body-specific ('local') or whole ('general'). Local treatment was used for skin infections like lupus vulgaris, as Finsen did, while general treatment was used to treat conditions like rickets.

Home-use lamps came onto the market in the late 1920s; they were smaller than clinical lamps. Actually nurses also used home-use lamps to take into patients' homes when making house calls, because they were much more portable. It's important to keep in mind though that these lamps weren't in every home: only the wealthy could afford to buy these and run them; remember that few homes were wired for electricity at this time. The lower classes accessed light therapy via free clinics and hospitals, where larger clinical lamps were used.

‘Lord Mayor Treloar Cripples’ Hospital and Collage: the Light Department at Alton’, undated (mid-1920s) postcard. Dr. Tania Woloshyn’s own collection.

How was light therapy perceived by the wider culture?

Hmm, this is a hard question, and one that takes a whole book to address! Broadly speaking, I would say that it was whole-heartedly accepted by the public, who greatly deferred to medical and scientific authorities. Light therapy (especially phototherapy) was understood to be cutting-edge medicine, and the lamps themselves were rather intimidating and impressive technological objects. In the UK popular newspapers like the Times constantly featured articles about, for example, the opening of the latest clinic - usually involving a member of royalty or civic importance. In France, a new law in 1936 allowing paid holiday leave for the working class meant that beaches were covered by swarms of sun-worshipping tourists during the summer months.

What surprised you most whilst researching your book on light therapy and visual culture?

It shocked me to learn that doctors were already making the link between ultraviolet light (sunlight more broadly) and cancer already by the late 1910s and early 1920s. Indeed by 1928 it had been proven in a laboratory, using mice. But no one really took it seriously until the 1940s, when wider interests in 'radiation' dominated politics and science.

Above: Retro 1950s British desk lamp by Pifco

What about light therapy today?

'Light therapy' today has a messy definition, in part because - as I argue in my book - it has a messy past! The kind of gadgets we see advertised in magazines or online retailers come in many different shapes and sizes. Some are used to treat SAD, whether sitting in front of them for a few minutes a day or as alarm clocks simulating the dawn, and I think they typically use blue and violet light - or even a broad white spectrum - to stimulate the body. These lamps shouldn't cause sunburn, and are therefore different to tanning beds and upright lamps. There are also infrared lamps used to treat wrinkles, acne and scarring.

Tell us about your converted heat lamp…

My converted 1920s Sollux has pride of place in my home. It makes a beautiful reading lamp, now that it has a normal bulb inside it! Guests are always struck by its unusual appearance and to learn of its age: the refurb was so well done that it is hard to believe it is almost 100 years old!

You might also like

A Modern Lounge: Creating a room to entertain

Whether it's a lavish dinner party or a cosy night in, let us guide you through how to use vintage lighting to create a multifunctional space in a flick of a switch with our new collection, The Lounge.

skinflint joins 1% for the Planet

Each year we'll be donating 1% of sales to a range of carefully considered nonprofits, creating positive environmental impact and change.

SustainabilityRemodelista: Kitchen of the Week

Our vintage Czech hotel pendant lights have received lots of attention after featuring in US online-magazine Remodelista’s ‘Kitchen of the Week’.

In the press